The idea of beaming solar power down from space might seem like something out of a sci-fi movie. But new legislation in Congress, a funding announcement from the UK government, and the first successful test of the technology all suggest its moment may be coming.

Getting your solar energy directly from space makes a lot of sense. The atmosphere doesn’t get in the way, and there’s no day and night so you can generate power around the clock. But to produce significant amounts of electricity you need to get a huge amount of equipment into orbit, which has historically been prohibitively expensive.

Rapid reductions in the cost of launches and the advent of new rockets that can carry much greater loads like Space X’s Starship are starting to change the calculus, though. And a growing number of governments are getting serious about turning to space in their quest to slash their carbon emissions.

Last Tuesday, UK Energy Security Secretary Grant Shapps announced £4.3m in funding for several projects aimed at developing the underlying technology required to make space-based solar power feasible. The following day, an amendment was added to a bill before the House of Representatives instructing NASA to work with the US Department of Energy on the technology.

“A lot of the technology that once made this source of energy the work of science fiction is now much cheaper, and easier to deploy than ever, putting it within reach,” said representative Kevin Mullin, D-Calif, who proposed the amendment, at a meeting of the Science, Space, and Technology Committee.

It’s not just falling launch costs that are renewing interest in the technology. In January, Singularity Hub reported on the launch of a space mission designed to test key bits of hardware that will be necessary. Earlier this month, the team from Caltech behind the launch reported that, for the first time, a small amount of energy had been beamed down to Earth from a satellite.

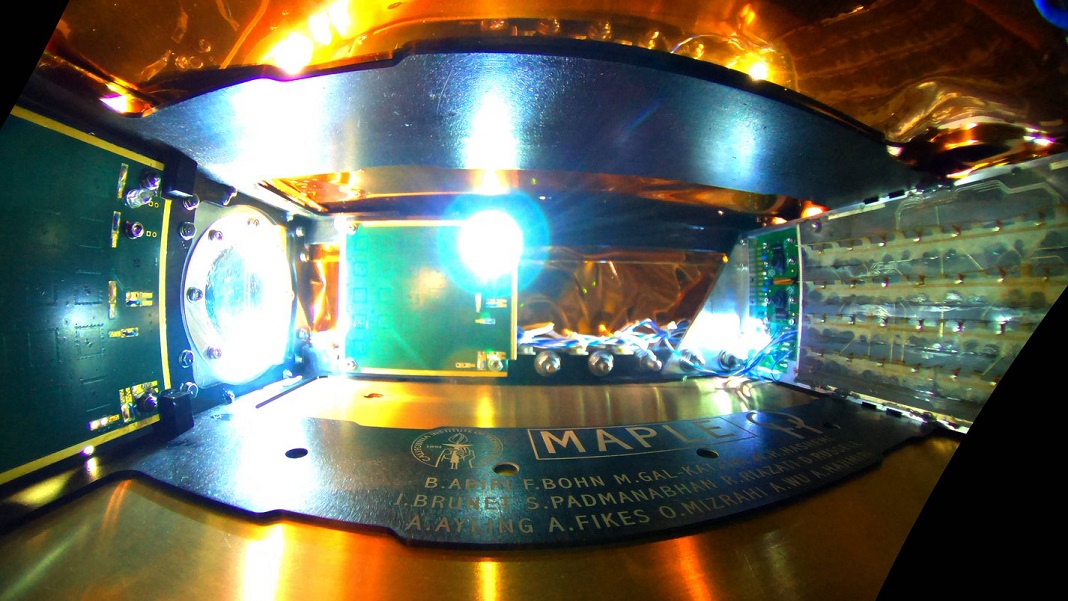

The mission features several separate experiments designed to test different components, but the recent success involved the microwave transmitter. The device can direct a beam of microwaves in different directions by varying the timing of signals sent to its 32 antennae, and the team used this to transmit 200 milliwatts of power to a receiver at Caltech.

There’s still plenty of other bits of technology that need to be developed before an orbiting solar farm can become a reality, though. Aside from the antennae, the Caltech team will be testing a variety of different solar cells to see which can best survive in space, and also a lightweight device designed to unfurl a large, flexible solar panel.

The funding announced by the UK will be going towards developing some of the fundamental technologies required. The University of Cambridge and Welsh technology company MicroLink Devices UK have both received money to develop lightweight solar panels, while Queen Mary University in London has received backing to develop a long-range power transmission system.

Beyond the technology, more work also needs to be done to flesh out the feasibility and economics of space-based solar. The University of Bristol has received funding to develop a large-scale simulation that will help model the performance, safety, and reliability of the technology. Imperial College London, on the other hand, will use its grant to study the impact the technology could have, including how it could be integrated onto the grid.

But the combination of space technology and solar power is an obvious one, Mamatha Maheshwarappa, from the UK Space Agency, said in a press release. “Space technology and solar energy have a long history—the need to power satellites was a key driver in increasing the efficiency of solar panels which generate electricity for homes and businesses today,” she said.

While the amendment passed in the US House doesn’t entail any funding, it’s the first time the topic has been addressed legislatively since the 1970s. And there is growing momentum in the US, with NASA revealing last year that it had launched a study into space-based solar that is expected to be published in the coming months.

Lots of work remains to be done, and space-based solar may not be the silver bullet that saves us from climate change given how long it would take to develop and deploy. But the prospect of tapping more directly into the sun’s plentiful energy seems increasingly feasible.