In Short : SpaceX, the aerospace company founded by Elon Musk, has successfully launched the world’s first satellite capable of pinpointing carbon emissions from space. The satellite, named Sentinel-6 Michael Freilich, was launched on a Falcon 9 rocket from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California.

In Detail : Previous satellites have had a hard time trying to detect individual human-made sources of the most common greenhouse gas.

The world’s first satellite capable of detecting industrial sources of carbon emissions from space has just reached orbit — and it promises to be a game-changer.

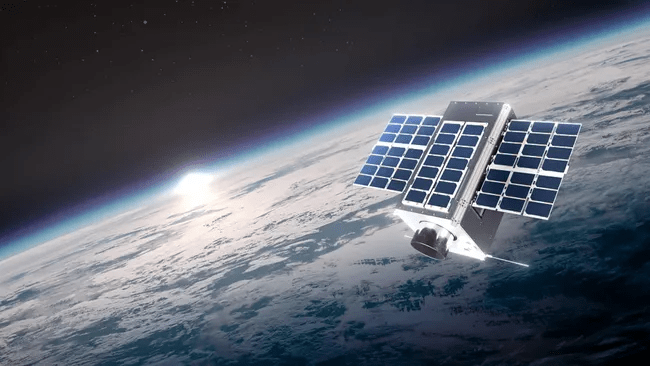

The satellite, called Vanguard, will be able to detect emissions from individual coal and gas-fired power plants, large oil refineries, steel plants and other polluting industrial facilities. Vanguard launched on SpaceX’s Transporter 9 rideshare mission on Saturday, Nov. 11, together with two new methane-monitoring satellites of the GHGSat constellation.

The Vanguard satellite will orbit Earth at the altitude of 300 miles (500 km), imaging each spot on the planet every two weeks.

Developed by Montreal, Canada-based firm GHGSat, the satellite uses a novel instrument invented by the company and previously fine-tuned on its existing fleet of satellites that monitor emissions of methane, another dangerous greenhouse gas. GHGSat launched its first methane-monitoring satellite, a demonstrator called Claire, in 2016, and has since built a reputation for its ground-breaking ability to detect methane leaks from gas pipelines, stealthy emissions from landfills and even burping cows.

The team has now retrained their instrument, an innovative device called the Wide Angle Fabry–Pérot Interferometer, to spot and quantify emissions of the most common greenhouse gas, carbon dioxide.

GHGSat’s President Stephane Germain explained that the instrument detects the presence of the greenhouse gases by analyzing the unique light absorption pattern of a column of air above every spot on Earth. Each chemical molecule absorbs light differently, and by analyzing the measurements, researchers can detect the presence and quantify the amount of the specific gas they are interested in.

“We are looking for very specific absorption lines,” Germain told Space.com. “The amount of the gas in the atmosphere is then proportional to the amount of absorption of light at those specific wavelengths. So, we can quantify the concentration of carbon dioxide in every pixel of our field of view.”

Because concentrations of carbon dioxide in Earth’s atmosphere are overall much higher than those of methane, other satellites have previously had a hard time trying to detect individual human-made sources of the most common greenhouse gas.

However, in January this year, researchers using data from NASA’s Orbiting Carbon Observatory 2 (OCO-2) were able to measure fluctuations in carbon dioxide emissions produced by Europe’s largest coal-fired power plant. This was a global first. But GHGSat’s new satellite will provide such measurements on a daily basis.

“We have a 12 by 12 kilometer [7.5 miles by 7.5 miles] field of view where you’ve got more than a million pixels, or [carbon dioxide] concentrations,” said Germain. “We quantify the concentration in every field and if we see high concentrations in a particular location that are decreasing downwind from that location, that’s a tell-tale sign there must be a source.”

By comparing the data with visual images of the same location, researchers can pinpoint each individual source of carbon emissions.

Earth-observation consultant at TerraWatch Space Aravind Ravichandran said that while the technology is ground-breaking, GHGSat might find less demand for their space-based measurements of carbon dioxide than they have for methane.

“It is relatively less disruptive compared to methane, which has been the holy grail really,” Ravichandran told Space.com. “We know most of our carbon dioxide sources. So, unlike methane, which gives new info on where the sources are, with carbon dioxide it is a case of verification of the major emissions.”

Germain confirms that GHGSat’s primary interest in methane was motivated by the lack of other options to detect leaks of the gas on a global scale.

“There was a clear, urgent commercial need for monitoring methane emissions everywhere around the world,” Germain said. “A significant part of the methane emissions is what we call fugitive emissions, which means that you don’t necessarily know where and when they are going to pop up. So, satellites are ideally suited for that kind of use case.”

GHGSat currently operates a constellation of nine methane-monitoring satellites, selling their data to oil and gas companies that want to reduce their carbon footprint and government regulators interested in keeping tabs on polluters worldwide. The regulators are the most likely customers for data from the new satellite.

Currently, countries self-report their carbon emissions based on the performance of their economy. Independent eyes in space will help validate the existing estimates.