Wind and solar projects have faced complaints from communities and in protected areas, as experts call for stronger planning laws and impact assessments

Sitting a few metres from the Girasol Solar Park, the largest photovoltaic power plant in the Dominican Republic and the Caribbean, Carlos Suazo claims that this majestic infrastructure is responsible for the increased heat in his community.

Like Suazo, several other residents in Yaguate, a town in the southern province of San Cristóbal, claim that temperatures here have increased due to the presence of more than 268,000 solar panels next door to their homes.

The 120-megawatt facility is one of nine photovoltaic plants in the Dominican Republic, where recent years have seen a “boom” in the development of solar and wind energy projects, partly due to the rush to reach the national goal of 25% of electricity generated from renewable sources by 2025, up from around 17% in 2021.

To date, the Dominican Republic has 10 wind farms and nine solar plants in operation, as well as one biomass plant. As of September 2023, these energy sources totalled 1.1 gigawatts and represented 19% of the total installed capacity, positioning the country as a leader in renewable energy in the Caribbean.

In addition, the National Energy Commission (CNE) reported in April that 18 solar plants and two wind farms were under construction and will come into operation by 2025, with these two sources’ share in the National Interconnected Electricity System (SENI) alone expected to reach 25%.

But despite the giant strides the country has made, major obstacles remain. Most of these projects have been developed prior to the country having a land-use planning law, which would allow for a thorough assessment of their potential impacts on people, agricultural land or protected areas.

“Until now, solar and wind energy projects [in the Dominican Republic] have been located based on high rates of solar radiation and high rates of wind load, but without taking into account fundamental aspects of territorial planning, environmental impact and urban or agricultural expansion,” says Osiris de León, a geologist and member of the Academy of Sciences of the Dominican Republic.

So far, projects have only required the approval of the ministries of the Environment and Natural Resources, Agriculture and the CNE, which is the body in charge of the operational management of energy policies. It also oversees monitoring and compliance with the country’s 2007 law that provided incentives for the development of renewable energy.

It was not until 2022 that the Dominican state enacted the Law on Territorial Planning, Land Use and Human Settlements (No. 368-22), and its implementing regulations have not yet been published.

Erick Dorrejo, director of Border Zone Development Policies of the Ministry of Economy, Planning and Development (MEPyD) of the Dominican Republic, explains that a commission is currently working on the implementing regulations for the recent.

“The instruments foreseen in the law can contribute to establishing the ideal location for these projects and, at the same time, the spaces for separation from other identified uses in the territory,” Dorrejo added.

The absence, to date, of such regulations and adequate planning has caused anguish and discomfort for residents in the vicinity of some projects, who are feeling repercussions in their daily lives.

Residents claim climate and land impacts

The residents of Yaguate do not have a scientific explanation for what they claim is happening in their community. However, across the Caribbean on Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula, where renewable projects have previously been met with frustration from local communities, experts lend backing to their complaints.

Articulación Yucatán is a sustainable development organisation that campaigns for the protection of natural resources, and according to its transdisciplinary team, it is possible for photovoltaic plants to lead to heat increases.

“Photovoltaic systems require the removal of vegetation from large areas and therefore involve the clearing or deforestation of hundreds of hectares,” the organisation’s Jazmín Sánchez Arceo, an environmental engineer, anthropologist Ivet Reyes Maturano, and physical chemist Rodrigo T. Patiño Díaz explained to Diálogo Chino in a joint response.

This clearance has an impact on soils, which when degraded have a reduced capacity to retain water, which in turn can affect humidity and can warm the surface temperature.

Residents of Yaguate have also complained over the loss of access to land and space for agriculture following the installation of the Girasol Solar Park. They say it took away an area that was used for sugar cane production, which, although they did not own it, they could use to raise animals and travel to other locations.

“Before, you could walk around like it was nothing, but now you can’t go there,” says Bolívar Rodríguez, another resident of the community. “To enter you have to ask for a permit. If you go through the gate, after two minutes the security comes to ask what you are doing there.”

The solar park’s land, which covers an area of just over 3 km2, previously belonged to CAEI, a sugar-focused agribusiness, according to a 2020 document relating to the facility issued by SIE, the state electricity regulator. In 2021, the National Energy Commission signed a 30-year concession with Dominican public-private power firm EGE Haina to build and operate the solar facility, with the project inaugurated in June of that year. The company currently operates four wind farms, and oversees two more solar parks across the country.

At some points of its perimeter, the Girasol Solar Park is approximately 40 metres from residential buildings and community areas, which has also drawn criticism from residents. However, under Dominican law there has been no minimum distance established to be kept between this type of infrastructure and inhabited areas.

Ahead of the park’s construction, the SIE’s 2020 resolution referred only to the project’s proximity to a cemetery, and although it mentions it as “a sensitive part that impacts the project”, it indicates that the petitioner informed that a distance of about 100 metres would be kept “to have a good margin of tolerance”.

When approached for response on community complaints, EGE Haina did not comment directly on the distance between the park and buildings. However, the company’s senior director of communications and sustainability, Ginny Taulé, told Diálogo Chino that three separate public hearings were held prior to the solar park’s construction with no opposition raised, and that the project was positively received by local authorities and community members.

The EGE Haina representative also rejected residents’ claims that the solar park’s panels were responsible for any notable increase in temperatures in the Yaguate area, pointing instead to broader changes in climate. “June and July 2023 have been the hottest months in the [recorded] history of humanity, this data is easily verifiable and is related to global warming and the effects of climate change, not to renewable energies that constitute a response to this situation,” Taulé said.

Government entities SIE and CNE were approached for comment on Yaguate residents’ complaints, but at the time of publishing, no response had been received.

Worries for wildlife

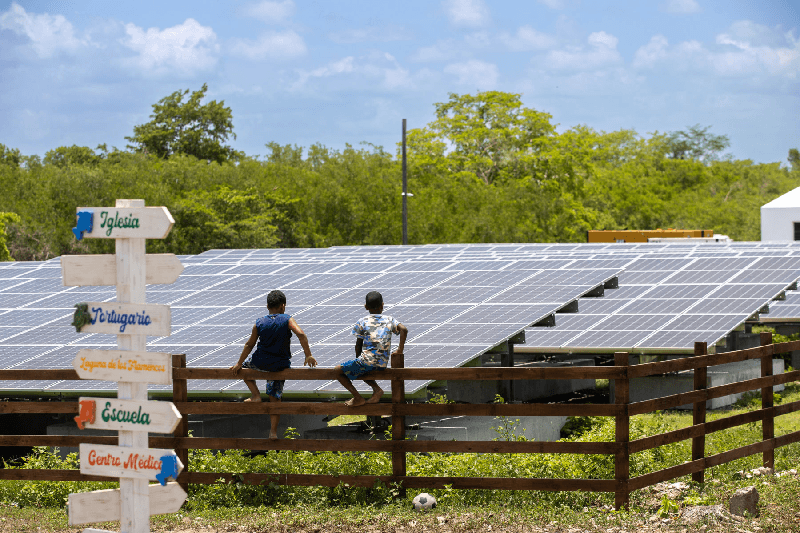

At the eastern end of the country, in the community of Mano Juan – located on the small island of Saona that forms part of the idyllic Cotubanamá National Park – Pelagio Paulino cannot hide his sadness at the construction of a solar park, built to provide electricity to local residents, and boost “economic and social development of the community”, its owners say.

Paulino – better known as Negro, the protector of the turtles – worries that the 5 MW facility, opened this year by the Bayahibe Electricity Company (CEB), will affect the three species of turtle that nest in the area, and which he has been trying to protect for years.

“We have a lot of problems with their behaviour. When the turtles find the lights they get disorientated, leave a nest here and go somewhere else. It’s unusual behaviour,” he explains.

The species that nest on Saona Island are hawksbill turtles (Eretmochelys imbricata), green turtles (Chelonia mydas) and leatherback turtles (Dermochelys coriacea). The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) lists all three species as endangered or vulnerable.

Dominican marine biologist Omar Shamir explains that Paulino’s claims may be accurate, and that artificial light is known to affect sea turtle species, which take signals for movement from light sources. Studies from around the world, including from across the Caribbean in Venezuela, have previously documented impacts on the nesting of sea turtles. Such research has found that artificial lighting near beaches – such as that found provided by the new supply from the Mano Juan solar facility – causes hatchlings to become disoriented and divert them away from their path to the sea.

Shamir points out, however, that it is necessary to examine in greater detail whether the lights from the facility, the houses and businesses of Mano Juan, a community of about 500 inhabitants, reach the areas where the turtles nest.

Meanwhile, Eleuterio Martinez, a tropical ecologist and president of the Dominican Academy of Sciences, alleges other serious issues with the solar project, claiming that its construction within a protected area violates the country’s laws and constitution.

“We do not know under what rule, what authorisation, or who has so much power to give a permit of that nature on Saona Island,” he said. “This must be taken to the ultimate consequences. This must be taken to the constitutional court because it is a physical attack on property of the Dominican Republic and that is not allowed.”

When approached over these issues, Federico Franco, vice-minister of protected areas and biodiversity at the Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources, said the solar facility had existed at Mano Juan since 2016 but was not functional, only entering into operation this year after work to upgrade it. “What was done in alliance with [CEB’s parent company] CEPM was to update the technology and complete what was missing,” he said. The minister did not address Paulino’s concerns around sea turtles, nor comment directly on the agreement or permits for the project. CEB was also approached for comment, but at the time of publishing, no response had been received.

Stronger evaluation needed

The generation of energy from renewable sources such as solar and wind is considered one of the best options for mitigating greenhouse gas emissions and thus meeting climate goals. However, these cases highlight the potential conflicts they can bring about, experts say, and point to the need for states to establish strong laws and regulations to locate and monitor and energy projects.

However, for Luis Carvajal, a biologist also of the Academy of Sciences, the problem is not the lack of a territorial planning law, but that in many cases the environmental studies that support them are not sufficiently rigorous.

“Many environmental studies lack rigidity. The terms of reference are insufficient or the level of review carried out by the ministry [of Environment and Natural Resources] is not adequate,” he says. Carvajal says the country must continue to support renewable energies but be more rigorous in the evaluation of their potential negative impacts, no matter how minimal they may be, as there have been what he describes as “structural failures” regarding environmental permits.

“Here, very often, technicians have been sanctioned and even excluded from the ministry [of Environment and Natural Resources] for opposing projects based on technical validations because there is a personal, political interest or officials with the power to impose it. And that has happened historically,” says the academic.

Osiris de León suggests that the expansion of renewable energy projects must be adjusted to the new territorial planning law, the national system of protected areas, and municipal and provincial strategic plans, to help avoid future conflicts.

The experts from Articulación Yucatán similarly point to an urgent need to improve socio-environmental evaluations, for impact studies to be made public, transparent, and free from influence from projects’ developers. Moreover, they add, projects must take into account local needs and priorities.

“We believe that the current logic for locating this type of megaprojects must be overcome, thinking about the different territories, what type of resources they have and what type of development they want from the local level.”