Around 95% of buyers today don’t meet new standards on carbon offsets

The $2 billion voluntary carbon-offsets market has suffered allegations that many credits don’t deliver the emissions cuts they promise, but multiple efforts to rebuild credibility face an uphill battle.

Recently the Commodity Futures Trading Commission said it would make policing carbon offsets a priority, Nestlé decided to leave the market and standard setters published guidelines that few existing buyers would meet. As things currently stand, only 5% of companies buying voluntary credits would meet the tough new standards on their proper use, according to Trove Research. It also estimates that less than 2% of projects issuing credits would comply with new standards for sellers—assuming the final rules coming soon are in line with the draft published in July 2022.

“The offset industry’s inability to self regulate has produced a slow-moving crisis,” said Danny Cullenward, research fellow at the Institute for Carbon Removal Law and Policy at American University. “Companies are asking whether the marketing benefits are worth the legal risks.”

Carbon offsets are part of nearly every scenario that keeps global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius. Initially popular with companies, they were seen by many, including U.S. climate envoy John Kerry, as a crucial way to fund climate action around the globe. Morgan Stanley estimated in February that it could be a $100 billion market by 2030.

However, over the past year the market’s credibility has suffered after a series of allegations that credits aren’t delivering on their emissions-reduction promises. It has left many companies with cold feet.

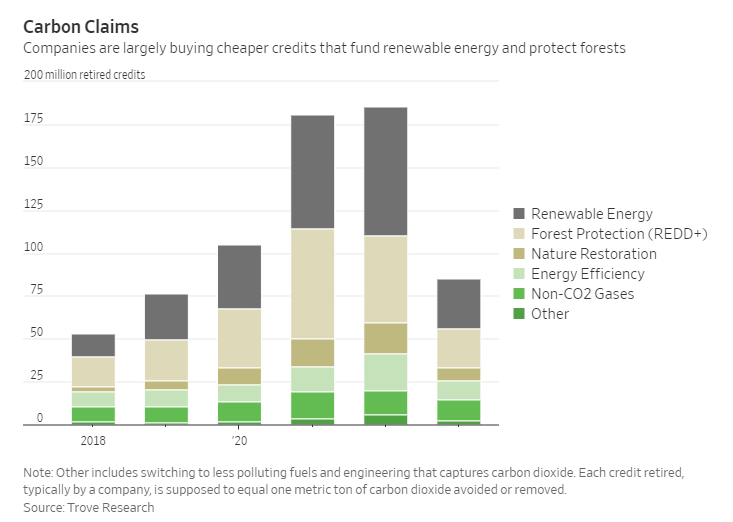

Each carbon credit is supposed to equal one metric ton of carbon dioxide avoided or removed from the atmosphere. Removal credits usually fund restoration projects such as tree planting, while the most common offset or avoidance credits fund energy-efficiency projects, renewable energy or protect forests. These so-called voluntary credits are separate and usually cheaper than government-regulated carbon trading that polluters pay for in the European Union and elsewhere. There are also some voluntary credits for mechanically removing CO2 directly from the air, which are currently much more expensive.

Nestlé is pulling out of carbon offsets and withdrawing carbon-neutrality claims for brands such as Nespresso, Perrier and San Pellegrino, to focus on investments that cut emissions in its supply chain and operations, a spokeswoman said. Airline easyJet and fashion brand Kering, have also decided to exit from the market completely.

Many companies are avoiding the market given the reputation risk and rising scrutiny.

In June, the CFTC—the federal regulator of derivatives—created an environmental task force focused on rooting out fraud in carbon markets. Earlier that month, the agency called for whistleblowers to expose misconduct.

“As carbon credit markets continue to grow, we will act to foster the integrity of these markets by fighting fraud and manipulation,” CFTC Enforcement Director Ian McGinley said.

There has been a flurry of efforts to rebuild the market’s credibility.

U.N. climate negotiators are hashing out rules for a global marketplace for carbon offsets under the Paris Agreement that companies and countries can buy from. Projects that get the go-ahead from governments could sell their credits in the marketplace, but agreement still hasn’t been reached on what kinds of projects will qualify.

Two voluntary standard setters are racing to re-establish credibility. The Integrity Council for the Voluntary Carbon Market, or ICVCM, in March released its first set of rules for suppliers of credits covering what makes a high-quality offset. It included requirements that third parties audit emissions claims and that credit issuers show they can track credits.

A parallel effort by the Voluntary Carbon Market Integrity Initiative, or VCMI, is setting rules for the buyers of offsets. It released rules in June outlining how companies should and shouldn’t use carbon offsets, which required any company buying offsets to disclose its full emissions, its short- and long-term climate targets and its emissions-reduction spending, or to explain why it wasn’t publishing the information.

The new standards have set a high bar and that is good because the market has plenty of examples of poor corporate climate claims and low quality credits, Trove Research Chief Executive Guy Turner said. But rule setters also need to ensure that they don’t alienate well-intentioned companies, he said.

“Climate commitments of firms and their actions are voluntary, and they can choose to not do anything,” Turner said.

In response, VCMI Executive Director Mark Kenber said the rules follow commonly accepted best practices and give companies guidance to make credible claims in the future.

“There will be more work going on this year to address critical issues that companies face and questions that we are yet to answer but have been carefully consulting the industry on,” Kenber said.

Still, estimates on how many credits are high quality under the ICVCM are premature because a more detailed set of standards is coming later this year and the group will be conducting its own review of the market, said William McDonnell, chief operating officer of the organization.

“Our initial review of the market suggests that there are many good examples of robust standards on additionality, quantification and permanence, but that they are not all consistently applied, ” McDonnell said.