A dozen U.S. states, from California to New York, have joined dozens of countries, from Ireland to Spain, with plans to ban the sale of new cars with an internal combustion engine (ICE), many prohibitions taking effect within a decade. Meanwhile, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), in a feat of regulatory legerdemain, has proposed tailpipe emissions rules that would effectively force automakers to shift to producing mainly electric vehicles (EVs) by 2032.

This is all to ensure that so-called zero-emission EVs play a central role in radically cutting carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions. To ensure compliance with ICE prohibitions and soften the economic impacts, policymakers are deploying lavish subsidies for manufacturers and consumers. Enthusiasts claim that EVs already have achieved economic and operational parity, if not superiority, with automobiles and trucks fueled by petroleum, so the bans and subsidies merely accelerate what they believe is an inevitable transition.

It is certainly true that EVs are practical and appealing for many drivers. Even without subsidies or mandates, millions more will be purchased by consumers, if mainly by wealthy ones. But the facts reveal a fatal flaw in the core motives for the prohibitions and mandates. As this report illustrates:

No one knows how much, if at all, CO2 emissions will decline as EV use rises. Every claim for EVs reducing emissions is a rough estimate or an outright guess based on averages, approximations, or aspirations. The variables and uncertainties in emissions from energy-intensive mining and processing of minerals used to make EV batteries are a big wild card in the emissions calculus. Those emissions substantially offset reductions from avoiding gasoline and, as the demand for battery minerals explodes, the net reductions will shrink, may vanish, and could even lead to a net increase in emissions. Similar emissions uncertainties are associated with producing the power for EV charging stations.

No one knows when or whether EVs will reach economic parity with the cars that most people drive. An EV’s higher price is dominated by the costs of the critical materials that are needed to build it and is thus dependent on guesses about the future of mining and minerals industries, which are mainly in foreign countries. The facts also show that, for the majority of drivers, there’s no visibility for when, if ever, EVs will reach parity in cost and fueling convenience, regardless of subsidies.

Ultimately, if implemented, bans on conventionally powered vehicles will lead to draconian impediments to affordable and convenient driving and a massive misallocation of capital in the world’s $4 trillion automotive industry.

Introduction: Reactionary Revolutions

Few doubt, even if some lament, the centrality of the automobile in modern society. As the late MIT historian Leo Marx put it: “To speak, as people often do, of the ‘impact’ of . . . the automobile upon society makes little more sense, by now, than to speak of the impact of the bone structure on the human body.”[1] For more than a century, policymakers have encouraged, facilitated, regulated, and taxed the production and use of automobiles.

But now, policies unprecedented in scope and consequence are planned to ban the sale of the type of vehicle that 99% of people use—that is, vehicles powered by an internal combustion engine (ICE). Instead, government policies are being launched to mandate, directly and indirectly, electric vehicles (EVs).

Rarely has a government, at least the U.S. government, banned specific products or behaviors that are so widely used or undertaken. Indeed, there have been only two comparably far-reaching bans in U.S. history: the Eighteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which prohibited the consumption of alcohol (repealed by the Twenty-First Amendment); and the 1974 law prohibiting driving faster than 55 mph. Neither achieved its goals; both were widely flouted, and the first one engendered unintended consequences, not least of which was criminal behavior.

The idea of banning the internal combustion engine (ICE)—or the de facto equivalent through Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) rules—emerges from the thesis that an “energy transition” eliminating hydrocarbon use is both necessary and inevitable. The ICE ban echoes other energy transition ideas but with an important distinction. Electricity production mandates, for example, that ban the use of coal and even natural gas “merely” raise costs, while the product that consumers use, kilowatt-hours, remains largely unchanged in its utility.[2] EVs, as we will explain, do not have the same utility and are neither operationally nor economically equal for most citizens. Nonetheless, hundreds of billions of dollars in taxpayer funds and corporate spending are now being directed at subsidizing and building EVs in concert with many near-term prohibitions on the sale of ICE vehicles.

Enthusiasts rightly credit Elon Musk with launching today’s excitement about EVs. Until the 2012 introduction of the Tesla S—coincidentally, exactly 100 years after Studebaker closed its EV production line, then the biggest EV producer—no company had successfully introduced a battery-only option for an on-road car. Nor, in a century, has any new car company succeeded in taking market share from the legacy competition. Last year, Tesla was the number-one luxury brand in the U.S., accounting for nearly one-fifth of sales in that coveted, profitable category. This was a laudable feat, even if that category accounts for less than 10% of overall car sales. Unsurprisingly, every luxury automaker has scrambled to offer an all-electric option.

We even see nonautomotive tech companies eager to join the fray in building luxury electric cars. Rumors continue that Apple will yet unveil an EV.[4] (Indeed, the company could leapfrog the manufacturing challenge by using 10% of its cash to buy an entire company such as Hyundai.) Xiaomi, China’s “Apple” and the world’s number-three smartphone maker, announced a $10 billion plan to form an EV subsidiary.[5] Meanwhile, conventional automakers have already brought to market more than 40 different EV models.

The arrival of useful EVs didn’t happen because of government mandates or incentives. It was made possible by the maturation of two enabling technologies that were invented in the mid-1970s. One of them, the now-famous lithium battery chemistry, was first identified by Stanley Whittingham, while he was working at Exxon’s New Jersey research labs. (Whittingham was one of three to later receive the 2019 Nobel Prize in chemistry.) The other, less well-known but pivotal (and contemporaneous), invention came from Jay Baliga, who, while working at GE’s R&D center, invented the IGBT, a new class of silicon transistor capable of managing high-power electrical flows. The IGBT made possible the compact, efficient digital control of electrical power critical for all EV drivetrains. Baliga received the 2015 Global Energy Prize for “one of the most important innovations for the control and distribution of energy.”

Useful EVs are undeniably a significant addition to the pantheon of options for consumers. But the rhetoric and policies about the inevitability of EVs for everyone emerge from myths, misperceptions, and hyperbole about the underlying technologies. The International Energy Agency (IEA), for example, begins its 2023 “Global EV Outlook” by touting that EV “markets are seeing exponential growth as sales exceeded 10 million in 2022” (emphasis added). The finger-on-the-scale and hyperbole surrounding EVs begin right there.

Hybrids, as IEA observes in a footnote, accounted for nearly one-third of those global EV sales. Hybrids, by definition, use combustion engines that policymakers are eager to ban. And, relevant to the IEA claim that EV sales have “profound implications” for climate goals, nearly two-thirds of global sales were in China, which is, a priori, a special case—not least because its current and planned coal-dominated electric grid has profoundly negative implications in neutering climate goals.

Nonetheless, the 7 million (non-hybrid) EVs sold globally last year did constitute a huge jump from the 3,000 units sold by Tesla in 2012. And, while only 10% of all EV sales were in the United States (two-thirds of which were Teslas), policymakers appear confident that the “exponential” growth of EVs will make bans and mandates politically palatable because of the EV’s ostensibly inevitable superiority.[11] Aside from the claim of clear superiority—an issue that is a key focus of this report—we note that rhetoric about growth in EV sales being remarkable or “exponential” itself isn’t supported by the history of consumers embracing other new category-creating cars.

It took six years after its introduction before Tesla sold its 200,000th car. Two years after Ford introduced its electric Mustang Mach-E, sales reached only 150,000 (now the distant second most popular EV in America).Compare that to 1983, when Chrysler invented the minivan, well-timed to meet a demographic shift; consumers bought more than 200,000 in one year. But the consumer adoption record belongs to the 1964 Mustang, another category-creating car and one well-timed to meet the demographic shift of that era. Ford sold 1 million Mustangs within 18 months.[13] It took Tesla 92 months to reach that number.

This report does not focus on whether EVs are a practical and appealing new category for many drivers. They are. The world will see tens of millions more EVs on roads even without government mandates. But in banning ICE cars and mandating the use of EVs, policymakers are explicitly betting on the truth of three crucial claims:

EVs will lead to “profound” reductions in CO2 emissions

EVs are now, or will soon be, cheaper than, and operationally equal to, ICE cars

There is a diminishing role for the automobile in modern times; in effect, there is a generational realignment in how citizens seek personal mobility.

All three are bad bets not supported by facts. Before turning to the realities of EV emissions, it is useful to consider the state of mobility as seen in U.S. driving trends. How much, where, and why people drive reveals the kinds of features actually sought in cars.

The Current State and Future of Personal Mobility

ICE prohibitionists are the same as, or at least intellectual fellow travelers with, those who claim that we’ve reached “peak car.” The argument here is that millennials (born 1981–96) and Gen Zs (born 1997–2012) don’t share the affection for cars of baby boomers (born 1946–64). The former two cohorts are ostensibly eager to embrace ride-sharing, bicycles, scooters, and mass transit. Headlines have touted that the “Western world has turned its back on car culture.”Goldman Sachs analysts write: “Millennials have been reluctant to buy items such as cars” and are “turning to a new set of services that provide access to products without the burdens of ownership, giving rise to what’s being called a ‘sharing economy.’” Pundits, especially post-Covid lockdown, intone that remote work will reduce the number of trips that people will take.

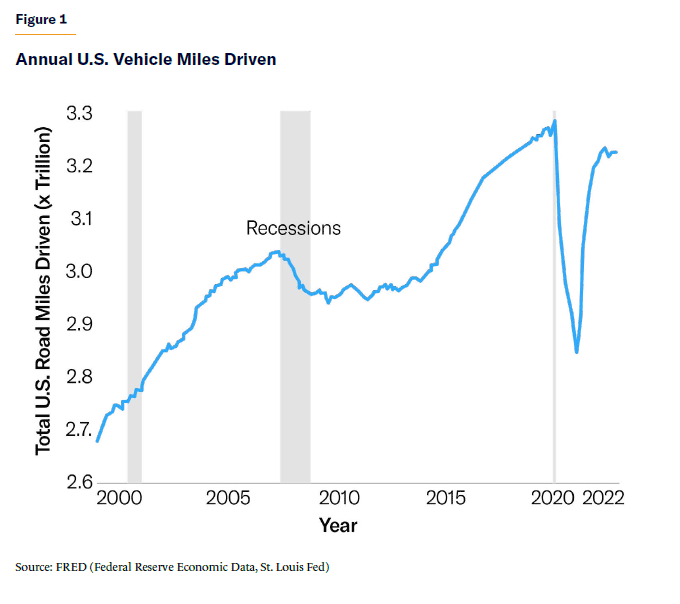

The data show that there is nothing to the belief that people in general, or in the rising generation, are giving up driving. Millennials—the first generation of the Internet era—now constitute the largest share of the population. It is thus notable, according to a recent MIT analysis, that, compared with boomers, millennials exhibit “little difference in preferences for vehicle ownership” and that “in contrast to anecdotes, we find higher usage in terms of vehicle miles traveled.”The share of cars bought by the yet-to-come-of-age Gen Zs has increased fivefold in the past five years. The data also show that once the 2008 recession ended and millennials found work, they bought cars and took to the roads along with everyone else, restoring and even somewhat accelerating the long-run growth in total vehicle miles driven on America’s roads. Only the Great Recession, and then the draconian pandemic lockdown measures, put temporary halts on that trend (Figure 1).

There is also a theory that the Internet causes a decline in car usage. Yet in 1999—at the first peak of digital enthusiasm—British sociologist John Urry presciently claimed that “travel through one medium overall increases travel through other media.” Looking at the long history of “automobility,” Urry wrote that “most car journeys now made were never made by public transport. Car drivers undertake connections with other peoples and places that were not undertaken previously.” And that’s what the record shows: both more driving and more digital traffic.

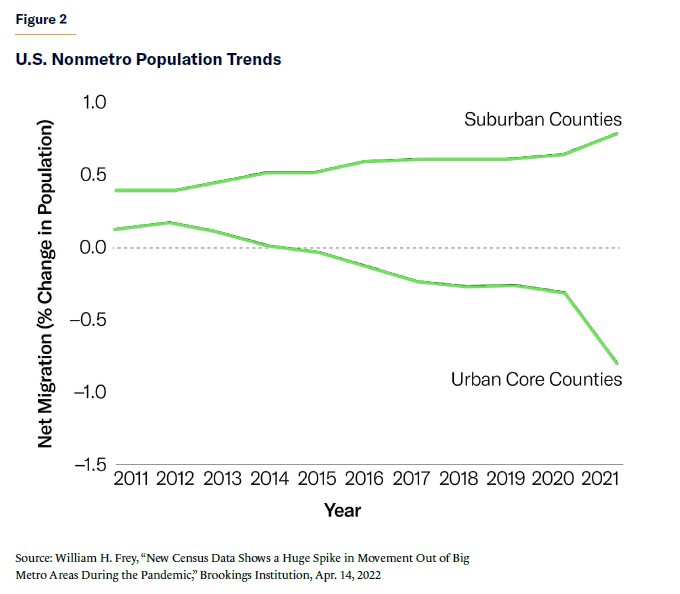

Another pillar of the peak-car thesis is that urbanization diminishes the need for cars, especially the need for people to drive long distances. Census data, however, show that the urbanization trend ended around 2010, when net migration to nonmetro and rural areas began.[21] While that trend was briefly accelerated by the lockdowns, the net migration to rural and ex-urban zip codes reverted to the trend “observed prior to the pandemic.” As one researcher noted in 2022, the de-urbanization trend could “become more commonplace” if late millennials and Gen Zs follow evidence suggesting that a rising share find “suburban and small-town life more attractive”(Figure 2).

Surveys reveal that not everyone who left the cities during the pandemic will move back, so the trend toward slow de-urbanization appears sticky. Other surveys also show that 60% of Americans claim that they prefer living in suburbs or rural areas and that, even if “money were no object,” only 40% would choose city life. A survey in early 2023 found that two-thirds of Americans would “consider moving to a rural home or a subdivision” if telecommuting were an option. Modern “zooming” has amplified Urry’s synergy of travel in the two different “media.”

One directly measurable effect of these trends is the boom in “super-commuters,” the nearly 5 million Americans now commuting some 90 minutes or longer.[26] Over the last decade, the super-commuting share of the workforce has increased threefold faster than the overall workforce. A 2023 survey by Upwork found that 41% of people are planning to move between two and four hours away from their current residences.Whether telecommuting while living and driving in spread-out ex-urban areas, or super-commuting to urban areas, there is a significant increase in the population living where distances traveled are radically greater than in the city.

Consumer preferences for comfort, size, convenience, and performance have driven a remarkable transformation in the average car purchased in America. Marked from 1975—the dawn of the heavy federal hand in vehicle energy-related regulations—the average automobile today has 100 more horsepower, weighs 1,000 pounds more, and has doubled in fuel efficiency. That last factor means that average CO2 emissions per mile have dropped by half.

Today, for the average household, personal mobility is the number-two expense after mortgage or rent. A car is the single most expensive product that 98% of consumers ever purchase. Banning ICE vehicles would constitute a takeover of one of the top three economic sectors of the nation, bigger than commercial banking or pharmaceuticals.

Now, in service of government climate strategies to achieve radical emissions reductions, consumers will need to adopt EVs at a scale and velocity 10 times greater and faster than the introduction of any new model of car in history. Policymakers are right about at least one thing: that won’t happen naturally from market forces or consumer preferences.

EV Emissions: Elsewhere, Unclear, and Maybe Unknowable

In contrast to cars with internal combustion engines, it’s impossible to measure an EV’s CO2 emissions. While, self-evidently, there are no emissions while driving an EV, emissions occur elsewhere—before the first mile is ever driven and when the vehicle is parked to refuel.

The CO2 emissions directly associated with EVs begin with all the upstream industrial processes needed to acquire materials and fabricate the battery. The received wisdom that EVs will have a “huge impact” on reducing emissions is, whether the claimants know it or not, anchored in assumptions about the quantities and varieties of materials mined, processed, and refined to make the battery.

The scale of those upstream emissions emerges from the fact that a typical EV battery weighs about 1,000 pounds and replaces a fuel tank holding about 80 pounds of gasoline. That half-ton battery is made from a wide range of minerals, including copper, nickel, aluminum, graphite, cobalt, manganese, and, of course, lithium. Critically, the combined quantity of these specialty and so-called energy minerals is 10-fold greater in building an EV, compared with an ICE car.

As researchers at the U.S. Argonne National Labs have pointed out, the relevant emissions data on such materials “remain meager to nonexistent, forcing researchers to resort to engineering calculations or approximations.” And, per IEA, data on the emissions intensity of specific minerals can “vary considerably across companies and regions.” That is a consequential understatement. The fundamental fact to keep in mind: every claim for EVs reducing emissions is a rough estimate or an outright guess based on averages, approximations, or aspirations. The estimates entail myriad known unknowns about what happens upstream to obtain and process materials to fabricate the giant battery. Those factors not only vary wildly but can be big enough, alone, to wipe out from one-half to all the emissions saved by not burning gasoline.

These features of EV emissions constitute a complete inversion of the locus and, critically, the transparency and certainty compared with combustion vehicles. For a conventional car, you know the emissions if you know the fuel mileage. The quantity of gasoline burned is directly measurable and forecastable with precision. Those CO2 emissions are the same regardless of when or where a car is refueled, or when it is driven. And while conventional cars also have “hidden” upstream emissions—the energy used to build the vehicle and create gasoline—these constitute only 10%–20% of these vehicles’ total life-cycle emissions.

The critical factor for estimating upstream EV emissions starts with knowing the energy used to access and fabricate battery materials, all of which are more energy-intensive (and more expensive) than the iron and steel that make up 85% of the weight of a conventional vehicle.The energy used to produce a pound of copper, nickel, and aluminum, for example, is two to three times greater than steel. Estimates of the aggregate energy cost to fabricate an EV battery vary threefold but, for context, on average, the energy equivalent of about 300 gallons of oil is used to fabricate a quantity of batteries capable of storing the energy contained in a single gallon of gasoline.

That so much upstream energy is necessarily used is understandable if one knows that hundreds of thousands of pounds of rock and materials are mined, moved, and processed to create the intermediate and final refined minerals to fabricate a single thousand-pound battery (see sidebar, “Sources of ‘Hidden’ Energy to Mine and Process 500,000 Pounds per EV Battery”).