U.S. power plant owners warned the Biden administration on Tuesday that its sweeping plan to slash carbon emissions from the electricity sector is unworkable, relying too heavily on costly technologies that are not yet proven at scale.

Top utility trade group the Edison Electric Institute (EEI) asked the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for revisions of the proposed power plant standards, which hinge on the widespread commercial availability of carbon capture and storage (CCS) and low-emissions green hydrogen, adding the agency’s vision was “not legally or technically sound.”

“Electric companies are not confident that the new technologies EPA has designated to serve as the basis for proposed standards for new and existing fossil-based generation will satisfy performance and cost requirements on the timelines that EPA projects,” EEI said in a public comment released on Tuesday on the agency’s deadline for feedback.

Resistance from the EEI and other energy-related groups poses a potentially big challenge to the administration’s climate agenda.

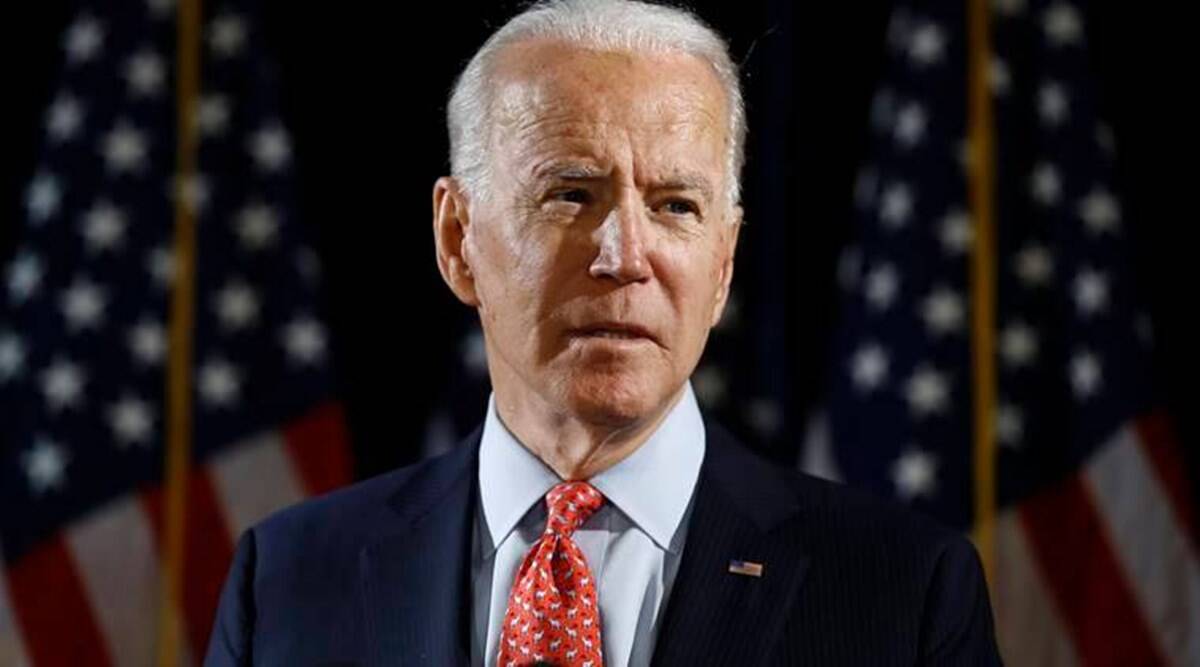

U.S. President Joe Biden has a goal to achieve net-zero emissions by 2035 in the power sector, the source of a quarter of the nation’s climate-warming gases. That target is a central part of Washington’s pledge to halve U.S. greenhouse gas output by 2030 as part of an international agreement to fight global climate change.

Proposed in May, the EPA plan would for the first time limit how much carbon dioxide power plants can emit, after previous efforts were struck down in court.

West Virginia, which led a lawsuit against the Obama-era Clean Power Plan, also said it and 20 other states were opposed to the rule because the standards would leave coal plant operators with no choice but to close.

The proposed limits for both new and existing power plants assume availability of CCS technology that can siphon the CO2 from a plant’s smokestack before it reaches the atmosphere, or the use of hydrogen as a fuel. The EPA said that last year’s passage of the Inflation Reduction Act, which subsidizes those technologies, makes them cost-effective and viable.

Environmental groups Clean Air Task Force and Natural Resources Defense Council said the proposal “provides generous lead times for implementation and compliance and will not cause reliability problems if finalized.”

Industry is particularly concerned about proposed standards for existing natural gas power plants, saying those facilities would be hard to retrofit with CCS, or hydrogen, due to space constraints and other limitations.

The biggest U.S. power grid operator, PJM Interconnection, and three other operators, serving a total of 154 million customers, raised concern about a scenario where “needed technologies are not widely commercialized in time to balance out large amounts of retirements” of dispatchable generation.

The grid operators, in a joint statement, urged the EPA not to adopt the plan before thoroughly looking into its impact on the reliability of electric grids, flagging its “chilling impact” on investment to maintain existing dispatchable units.

The EPA’s plan would require large existing gas-fired plants that run at least 50% of the time to install carbon capture by 2035, or co-fire with 30% hydrogen by 2032. EEI asked the agency to “repropose or significantly supplement” the proposed rules for existing gas plants.

One investor-owned utility, Baltimore-based Constellation, distanced itself from EEI’s position and said it supported the EPA’s proposed guidelines. The company said, however, that it was seeking improvements to the rule.

The National Rural Electric Cooperative Association, which represents 900 member-owned electric utilities, asked the EPA to withdraw the proposed rule, saying it would compromise reliability and affordability, said CEO Jim Matheson.

Labor unions, the United Mine Workers of America and the International Brotherhood of Electricity Workers, also called on the EPA to redo the rule and criticized its reliance on CCS, saying it puts jobs at risk.

The EPA’s proposal had been crafted to reflect constraints the Supreme Court imposed on the agency last year after it ruled that the Obama era’s Clean Power Plan went too far by imposing a system-wide shift from fossil fuels to renewable energy.