In Short : The shrinking glaciers in Switzerland pose a threat to the traditional way of life, as the impact of climate change becomes increasingly evident. As these glaciers diminish, they not only signify environmental challenges but also jeopardize the cultural and economic practices deeply rooted in the region, potentially leading to significant changes in the local way of life.

In Detail : For centuries, Swiss farmers have sent their cattle, goats and sheep up the mountains to graze in warmer months before bringing them back down at the start of autumn. Devised in the Middle Ages to save precious grass in the valleys for winter stock, the tradition of “summering” has so transformed the countryside into a patchwork of forests and pastures that maintaining its appearance was written into the Swiss Constitution as an essential role of agriculture.

It has also knitted together essential threads of the country’s modern identity: alpine cheeses, hiking trails that crisscross summer pastures, cowbells echoing off the mountainsides.

In December, the United Nations heritage agency UNESCO added the Swiss tradition to its exalted “intangible cultural heritage” list.

But climate change threatens to scramble those traditions. Warming temperatures, glacier loss, less snow and an earlier snow melt are forcing farmers across Switzerland to adapt.

Not all are feeling the changes in the same way in a country where the Alps create many microclimates. Some are enjoying bigger yields on summer pastures, allowing them to extend their alpine seasons. Others are being forced by more frequent and intense droughts to descend with their herds earlier.

The more evident the effect on the Swiss, the more potential trouble it spells for all of Europe.

Switzerland has long been considered Europe’s water tower, the place where deep winter snows would accumulate and gently melt through the warmer months, augmenting the trickling runoff from thick glaciers that helped sustain many of Europe’s rivers and its ways of life for centuries.

Today, the Alps are warming about twice as fast as the global average, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. In the past two years alone, Swiss glaciers have lost 10 percent of their water volume — as much as melted in the three decades from 1960 to 1990.

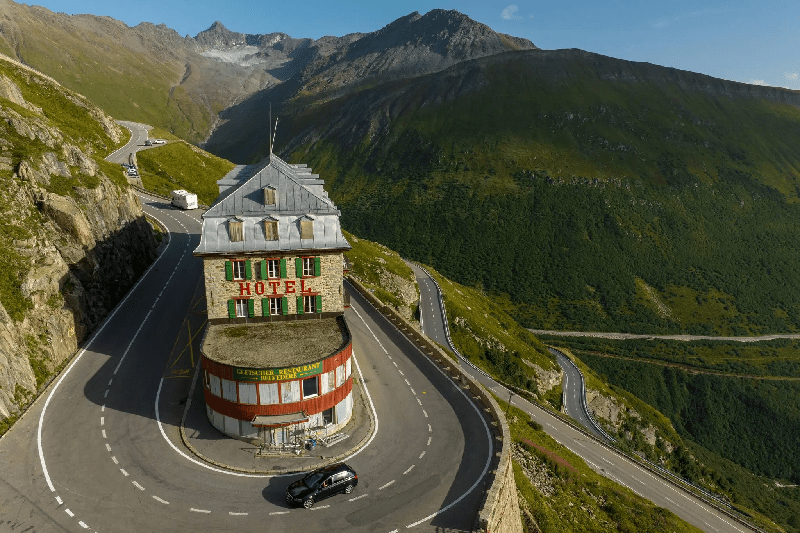

Since he started studying the Rhône Glacier in 2007, Daniel Farinotti, one of Europe’s premier glacier scientists, has seen it retreat about half a kilometer, or about a third of a mile, and thin, forming a big glacial pond at its base.

He has also seen the glacier — which stretches around nine kilometers, or about five and half miles, up the Alps near Realp — grow black as protective winter snow melts to reveal previous years of pollution in a pernicious feedback loop.

“The darker the surface, the more sunlight it absorbs and the more melt that’s generated,” said Mr. Farinotti, who teaches at ETH Zurich and who leads a summer field course on the glacier.

To get to the glacier from the road, his students walk across mounds of white tarps, stretched around an ice cave carved for tourists. The tarps can reduce annual melting by as much as 60 percent, but they cover only a minuscule portion of glaciers, and in places like ski slopes, where there is a private financial motivation.

“You cannot cover an entire glacier with that,” said Mr. Farinotti, who also works for the Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape Research.

The government is trying to address the changes and preserve Swiss alpine traditions, including with large infrastructure projects to take water to the top of mountains for animals grazing in the summer months.

For now, the traditions, while strained in places, continue. After three days of scrambling over rocky mountainsides and zigzagging stone steps, the first sheep in a giant herd of nearly 700 burst into view at the end of their “summering” last fall.

As a crowd of spectators cheered, some of the sheep pranced. Others stopped dead in their tracks and had to be coaxed along by herders in matching plaid shirts and leather cowboy hats, adorned with wildflowers and feathers.

The sheep had been living wild for more than three months — wandering around a high, vast wilderness penned in by glaciers. Their only contact with humanity had been the visits of a single shepherd, Fabrice Gex, who says he loses more than 30 pounds a season walking the territory to check on them.

“I bring them salt, cookies and love,” said Mr. Gex, 49.

To take them back to their owners, who are mostly hobby farmers, he was joined by a crew of herders — known locally as “sanner” from the Middle High German samnen, “to collect” — who arrive by helicopter.

The job is rough and paid modestly, but locally it is considered an honor to take part in a tradition first recorded in 1830, but that many believe started centuries earlier.

“To be a sanner gives you roots,” said Charly Jossen, 45, enjoying a beer with many of the spectators after completing his 11th season in the fall. “You know where you belong.” He had brought his son Michael, 10, for the first time.

Historically, the sanner would take the sheep across the tongue of the Oberaletsch Glacier. But the retreat of the glacier has long made that route too unstable and dangerous. In 1972, the community of Naters blasted a path into a steep rock face to offer the herders and sheep an alternative way home.

This season, the herders intend to push their return back by two weeks, said their leader, André Summermatter, 36.

“With climate change, our vegetation period is longer,” he said, standing in the ancient stone pen where the sheep are corralled at the end of their trek. “So the sheep can stay longer.”