-

Africa’s forests absorb 600 million tons of CO2 each year, more than any forest ecosystem on Earth.

-

Just 11% of carbon credits issued globally came from projects in Africa

-

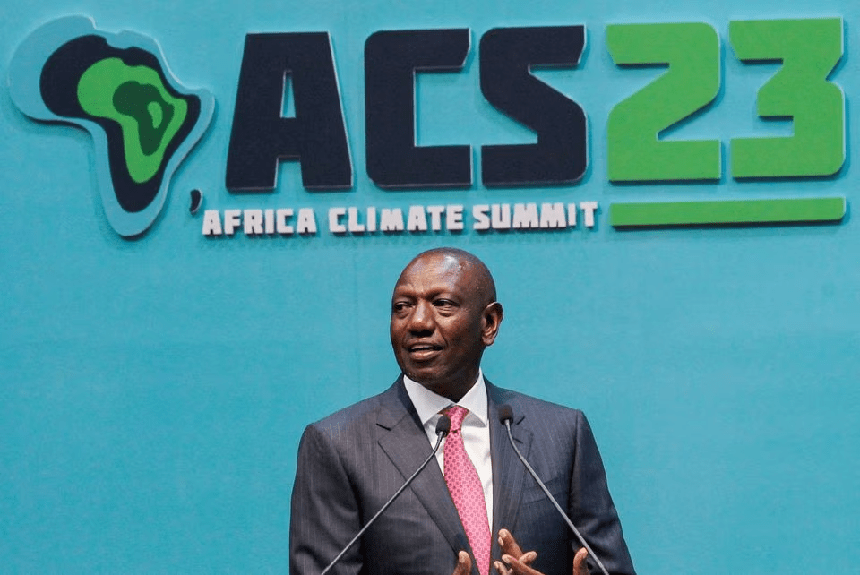

Kenya president William Ruto sees carbon credits as his country’s “next significant export”.

-

African Carbon Markets Initiative aims to produce 300 million carbon credits annually by 2030

-

Coup in Gabon, one of the leading proponents, has been a setback

The great rainforests of central Africa are one of the lungs of the world. The dense jungles in the Congo Basin teem with tens of thousands of species of plants and animals, and absorb 600 million metric tons of carbon each year on a net basis – more than any forest ecosystem on Earth.

Yet while these forests deliver a significant service to the whole planet in mitigating climate change, the question of how their value can be recognised is yet to be adequately addressed.

Africa, as is often noted, is the continent that bears the least responsibility for climate change. Fewer than 4% of emissions come from Africa, while the continent sequesters vast quantities of carbon through its rainforests, peatlands, mangroves, grasslands and other habitats.

Efforts to monetise these nature-based carbon removal services – partly with the aim of funding the conservation of Africa’s most important ecosystems – are still very nascent.

Yet policymakers are waking up to Africa’s potential role in carbon markets. Kenyan president William Ruto described carbon credits as his country’s “next significant export” at COP27 last year. The same event saw the launch of the African Carbon Markets Initiative (ACMI), with the aim of producing 300 million carbon credits annually by 2030.

So far, Africa has been punching below its weight in the voluntary carbon market. Only 11% of carbon credits issued worldwide between 2016 and 2021 came from projects in Africa.

The emergence of serious question marks over the creditability of carbon credit schemes, as highlighted by high-profile media reports throughout 2023, has not helped matters. While these concerns affect the voluntary carbon market globally, the real and perceived challenges with governance in Africa mean that nature-based carbon removals projects in the continent face heightened levels of scepticism.

Concerns over verification and validation of carbon credits is “one of the biggest choke points for the African carbon market”, says Annette Nazareth, chair of the Integrity Council for the Voluntary Carbon Market (ICVCM) and a member of ACMI’s steering committee. She adds that implementing the ICVCM’s Core Carbon Principles will rely on the scaling-up of validation and verification bodies in Africa that can ensure the integrity of carbon credits.

Doubts over project integrity are reflected in lower demand and lower prices for credits from Africa, adds Tariye Gbadegesin, co-chair of the Voluntary Carbon Markets Integrity Initiative (VCMI).

Gbadegesin predicts that prices for African carbon credits will remain very low without stronger “rules of engagement”. Robust integrity mechanisms are needed to serve as a “guard rail and a soft form of behavioural guidance”, thereby allowing carbon removal projects to charge higher prices, she says.

Kevin Juma, the lead forestry specialist for Africa at The Nature Conservancy, which is seeking to build a pipeline of investable nature-based carbon removals projects, agrees that stringent verification of claims made by projects offering carbon credits is essential to building confidence.

“The most fundamental thing is robust carbon accounting,” he says. “The claims of emissions reduction must be real. If a project is claiming to have reduced deforestation in that particular landscape, that must be qualified, and the claim must be real.”

For many years, the Central African nation of Gabon has been at the centre of discussions around the need to protect habitats that remove prodigious quantities of carbon from the atmosphere.

Forests cover around 90% of Gabon’s land area, and deforestation rates have generally remained low. The country is one of few in the world to be carbon net-negative, absorbing 100 million tons more carbon than it emits each year. The Gabonese government has long emphasised that conserving its rainforests is at the heart of its vision for national development.

Until, that is, President Ali Bongo was deposed in a military coup on August 30, ending his family’s 56 years in power and throwing Gabon’s commitment to carbon removals into confusion. Although early signs suggest drastic policy changes are unlikely under the new regime, the political upheaval will do little to build investor confidence. Shares in Gabon-based forest carbon developer Woodbois plunged by up to 17% on the day of the coup.

Even before the military seized power, Gabon was struggling to find a role in the voluntary carbon market. “Gabon doesn’t benefit from the current market systems,” Juma told The Ethical Corporation in an interview shortly before the coup. “It’s a high-forest, low-deforestation country. But the way the market works is to provide incentives to reduce deforestation.”

He adds that Gabon had “been making noise” in international forums, pointing out the risk of a “perverse incentive” in that climate finance benefits become more readily available only after deforestation accelerates.

Gabon did become the first African country to receive funding from the donor-led Central African Forest Initiative in 2021, after it was able to demonstrate that it had reduced deforestation rates.

The country also issued 90 million carbon credits last year through the United Nations’ REDD+ scheme in an attempt to monetise its rainforest conservation successes at the sovereign level.

However, reports over the following months suggested the issue had attracted very little demand. The Rainforest Foundation UK, a conservation NGO, warned in March that the credits were “likely worthless”. It cited the dubious method used to calculate the volume of avoided emissions between 2010 and 2018, and noted that the purchase of carbon credits would not produce any “additional” benefits. The credits were based on emissions that Gabon said had already been avoided due to policies dating from the early 2000s.

Prominent conservationist Lee White, who was Gabon’s environment minister for four years until the coup, has now appeared to partly concede that critics of the country’s approach to carbon credits had a point.

“Avoided deforestation is a good conservation strategy but a generally unreliable way of calculating carbon gains and really should not be used to create carbon credits,” he said in a statement issued after the government was overthrown.

Yet White defended the principle of issuing carbon credits at the national, rather than project, level. “To my mind, all project-based credits need to be nested within national reporting through the (UN Framework Convention on Climate Change) and need to clearly demonstrate additionality,” he said.

“We need to bring sovereign results and voluntary markets together if we are going to get out of the mess we are in right now, and thereby allow forest carbon to play its natural role in the fight against climate change.”

Despite the turmoil in Gabon, there are growing signs of momentum in Africa’s carbon market.

At the Africa Climate Summit in early September, a consortium of investors based in the United Arab Emirates pledged to purchase $450 million worth of African carbon credits via ACMI by 2030. “The UAE commitment is a significant win,” says Gbadegesin, noting that the investment will send a “very powerful” signal to the market.

But another Emirati investor, Blue Carbon, has courted controversy through several of its proposed climate finance investments in Africa. Under a draft agreement with Liberia, Blue Carbon would be handed a concession covering almost a 10th of the country’s territory. It would then sell carbon credits through restoring and preserving forestry within the concession area.

A coalition of NGOs issued a statement in July, warning that the deal poses a threat to the livelihoods of up to one million people and would extinguish community land ownership in certain areas. Blue Carbon has not commented publicly.

An approach resembling a colonial-era land deal appears ill-suited to a context where a genuine partnership with forest communities is clearly needed. Achieving “buy-in” from local communities is universally agreed to be key to the success of nature-based carbon removal projects.

“What is important is to involve the communities from the word go. They have been stewards of these resources for centuries,” says Juma of The Nature Conservancy. He emphasises that communities need to be intimately involved in land-use planning and must be rewarded for conservation successes through “proper benefit-sharing agreements”.

Valerie Morgan, head of the nature-based solutions technical team at carbon markets firm Climate Impact Partners, echoes this point. Climate Impact Partners mainly invests in reforestation or afforestation projects that can generate credits to be sold to companies seeking to fulfil net-zero commitments.

“The success of the project depends on the stewards of the trees that are planted,” says Morgan, who adds that finding a grassroots-level implementation partner is the top priority in any scheme. “The community buy-in is really important for us because in order for a project to be successful, it has to make sense for those who are planting the trees.”

On the frontlines of Africa’s fight against climate change, the need for collaboration between investors and communities becomes more urgent every day. Indeed, around 4 million hectares of forest are being lost each year on the continent, according to the U.N.’s Food and Agriculture Organization.

Finding ways for Africa to benefit financially from conserving and expanding its carbon sinks will be vital if the world has any chance of stabilising temperatures and averting the worst impacts of climate change.