It took hold in a world of low inflation and national confidence that is long gone

An English poet once wished for the bombing of Slough. Fans of Brentford FC hear the chant of, “You’re just a bus stop in Hounslow” from opposing crowds. And then there is Staines, the cradle of Ali G.

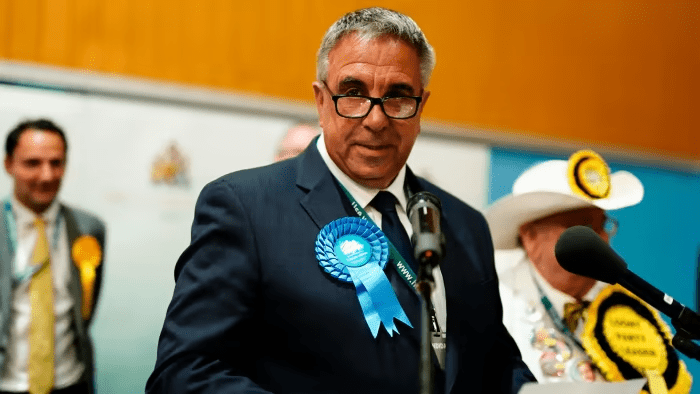

The towns and suburbs in the vicinity of Heathrow airport receive cruel treatment. Then, last month, one blasted itself on to the map and, I argue, into history. In Uxbridge, the Labour party lost a winnable by-election as locals mutinied against a green levy. Since then, Rishi Sunak, the Conservative prime minister, has said nice things about fossil fuels and confirmed plans for new drilling licences in the North Sea. Britain will look back on this seemingly banal election in this ostensibly quiet summer as the beginning of the end of its net zero consensus.

It was always paper-thin. In 2019, when Britain committed to net zero greenhouse gas emissions by the middle of the century, inflation was 2 per cent. A decade had passed since the previous recession. Had politicians been frank about the cost of the green transition, voters might have felt prosperous enough to pay it. Now? Not a chance.

Let us dispose of the idea that net zero is popular. Yes, in Ipsos surveys, voters endorse various green policies by supermajorities. But when a financial cost is attached to them, most are rejected. (“Creating low-traffic neighbourhoods”? 61 per cent against to 22 per cent for.) And that was in November 2022, after a summer of sadistic heat. Last month, a YouGov poll found that around 70 per cent of adults support net zero. If this entailed “some additional costs for ordinary people”, however, that share falls to just over a quarter. The wonder isn’t the political faltering of net zero. The wonder is that it took until Uxbridge.

This, I think, is the argument that a future Tory leader will make, and to great electoral effect: “Human-induced climate change is real and terrible. Don’t mistake us for denialists. But this is a medium-sized, post-industrial nation that accounts for around 1 per cent of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions. The ecological future of the Earth rests on giant middle-income countries, not on us.

“We should decarbonise. It would be weird to abstain from a technological crusade that America and the EU are going to make sure happens regardless. Britain has already committed a fortune in sunk costs. But a rush to net zero? That will cost you, dear voter, in ways that we politicians have obfuscated in the past. And what will that cost achieve? Not a material dent in the climate problem, but the setting of a moral example, as though India and China set their watches by us. Liberals forever accuse us on the right of overrating Britain’s sway in the world. Well, look who is grandstanding now.”

Faced with this message, what does Labour do? Allow itself to contest election after election as the expensive but righteous party? It is beyond imagining. And so the net zero consensus will break down from both sides. What was a hard and codified mission in 2019 might, over time, morph into something more like the Nato “guideline” to spend 2 per cent of national output on defence.

None of this is written with glee. The politics, not the intrinsic rightness, of net zero, is the subject of this column. And those politics seem untenable. The one thing holding net zero together is the stigma attached to coming out against it (Sunak, notice, still won’t do that) but this needn’t last.

Until well into this century, a “eurosceptic” was someone who wanted no part of the EU’s single currency or labour market rules. Outright rejection of EU membership itself marked one out as somewhat farouche. “In Europe”, a Conservative leader took care to stipulate at the 2001 election, lest people think him a freak, “but not run by Europe”. And he was still annihilated.

Over time, that taboo crumbled. When it did, lots of people realised that only a concern for social respectability had kept them from expressing their true preference. The past couple of weeks might have had the same liberating effect on net zero sceptics.

I so hate to use the worn-out Hemingway line about how a person goes bankrupt (“Gradually and then suddenly”). It is one step up from beginning a column with, “It is a truth universally acknowledged . . .” The trouble is that it really does capture something about politics. A change can be in the works for years, under the surface, until an event exposes, legitimises and accelerates it. Uxbridge feels like one such. The western fringes of London will have a new kind of infamy.